The Thermal Wall: Why Physics Mandates the Shift from Air to Liquid Cooling

The data center industry has hit a thermal wall. For decades, ambient air cooling was sufficient to maintain operational stability for the latest generation of server racks. That era is ending. In the last 24 months, the conversation has moved from viewing liquid cooling as a niche specialty to recognising it as an operational necessity.

This transition is driven by a collision between data center infrastructure and the immutable laws of thermodynamics. As silicon manufacturers push the boundaries of physics to power the AI revolution, traditional air cooling - while still sufficient for peripheral networking and storage - is physically incapable of extracting the primary thermal load generated by modern compute.

If modern chips are not adequately cooled, they suffer permanent degradation. This reality has led to the industry witnessing hyperscalers forced to pause five-year roadmaps and return to the drawing board.

The Physics of Extraction

To understand why air cooling has reached its limit, we must look at the fundamental thermal properties of the mediums we use to extract heat.

Cooling is ultimately a game of heat transfer. The efficiency of this transfer is dictated by density and specific heat capacity (ie the amount of heat energy a substance can hold).

Air is a gas with low density and a relatively low specific heat capacity (~1 kJ/kg). So, to remove significant heat, you must move massive volumes of it. Liquid, however, excels in both categories. Water has a much higher specific heat capacity and is far denser than air, making it approximately 3,000 times more efficient at carrying heat away by volume.

When rack densities were low, air’s inefficiency was manageable. However, today, relying on air is hitting a hard physical ceiling. Air lacks the thermal mass to absorb the intense heat flux of modern GPUs such as the NVIDIA GB300s and upcoming Vera Rubins. To keep up, fans would need to move air at velocities that are physically unachievable. We are facing a thermodynamic limit where air, regardless of speed, simply cannot absorb the heat fast enough to keep the silicon operational.

Data centers making the switch from air to liquid have a variety of liquids to choose from, each optimised for heat extraction based on the specific trade-offs an operator wishes to make. Options include water-based solutions (often mixed with glycol), which offer high thermal capacity but carry electrical risks, and engineered dielectric fluids.

The Source: Transistor Density and Power

The demand for this level of heat removal is a direct result of the strategy chip designers are using to fuel the AI revolution.

To achieve the exponential jumps in performance required for AI training, manufacturers are simply packing billions more transistors onto every chip. Before the AI boom (circa 2015), a standard high-end server chip contained roughly 2 to 3 billion transistors. Today, that number has exploded. In just two years, GPUs went from packing 80 billion transistors to over 200 billion on NVIDIA's Blackwell architecture.

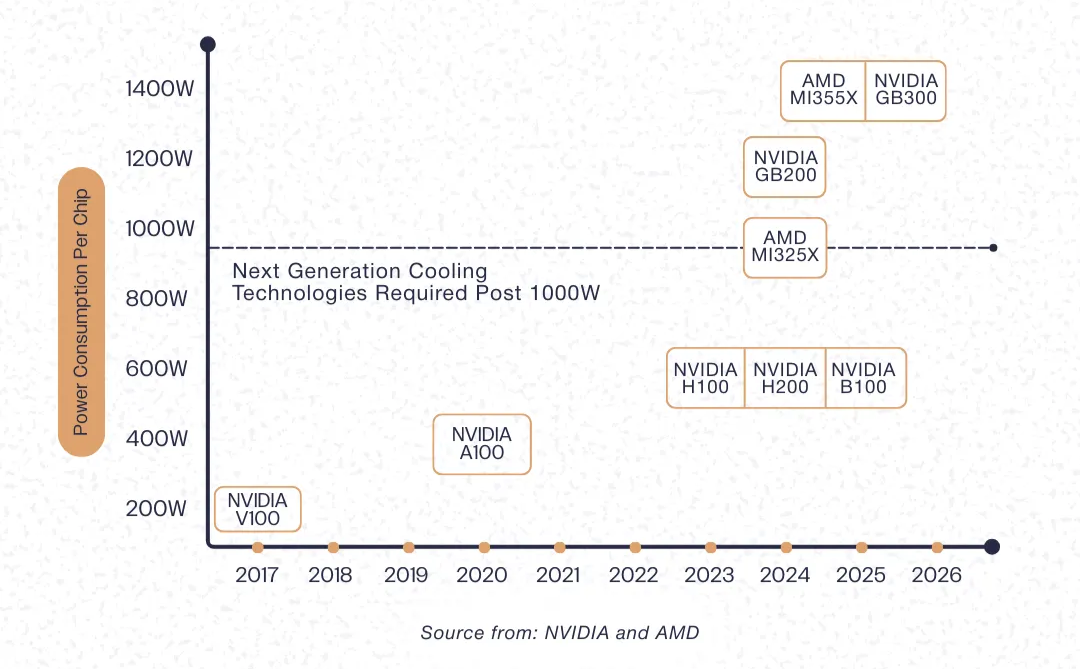

Powering this massive density of transistors requires significantly more energy. Consequently, Thermal Design Power (TDP) is skyrocketing. TDP represents the maximum amount of heat a chip generates that a cooling system must be able to dissipate. The latest generation of chips is breaking the 1,000W barrier per chip.

When you aggregate these chips into a single server and stack those servers into a rack, the thermal density skyrockets. Modern AI clusters are pushing rack densities toward 150kW and beyond. To contextualise this, a single high-density AI rack now consumes the power equivalent of a medium-sized residential neighbourhood.

But that is only the beginning. At GTC 2025, NVIDIA revealed its roadmap for the next-generation "Kyber" architecture. Designed to house 576 Rubin Ultra GPUs, this system is projected to push power density to 600kW per rack, effectively quadrupling the thermal load we are already struggling to cool today.

With chips packing billions more transistors, running at exponentially higher power, and crammed into ever-denser configurations, air simply cannot meet the thermodynamic needs of this environment - leaving liquid cooling as the only viable option to prevent these systems from overheating.

The Performance Imperative: Latency vs. Proximity

The shift to liquid cooling is also about preserving the performance of the AI models themselves.

AI models thrive on low latency. The speed at which data travels between GPUs determines the efficiency of training and inference. To minimise latency, chips must be placed physically close together. This creates a paradox for air cooling. To keep air-cooled chips operational, you must space them out to allow for airflow, which increases latency and degrades model performance. To maximise model performance, you must pack chips densely, which makes them impossible to cool with air. Liquid cooling resolves this paradox. By effectively managing the heat of high-density racks, liquid allows us to stack compute infrastructure in the tight configurations that AI algorithms demand.

The Operational Reality

We recognize that for data centre owners and operators, this transition is daunting. However, the risk of remaining with air is far greater. As silicon power continues to scale, facilities relying on legacy cooling will find themselves unable to support the hardware that defines the modern economy.

Physics mandates the future of compute must be liquid-cooled. The only question remaining for the industry is how quickly it can adapt.

Building the Future of Cooling

At Orbital, we are building the infrastructure to power this shift. Whether you require rapid deployment through our Nova Array modular data centres or advanced Direct-to-Chip (D2C) thermal solutions designed by AI, we help operators bridge the gap between legacy infrastructure and the AI era.

Ready to future-proof your facility? Contact our engineering team today to discuss how our physics-first approach can solve your high-performance cooling needs.